Etiology

Feline herpesvirus type 1 (FHV-1) belongs to the family Herpesviridae, subfamily Alphaherpesvirinae and genus Varicellovirus. Like other members of the subfamily Alphaherpesvirinae, they have a short replication cycle, lifelong latency induction (2), rapid cell-to-cell dissemination, and a tendency to induce cell lysis. Clinically, they tend to cause acute lytic disease followed by periods of latency and subsequent intermittent recrudescent disease (3).

The virus is susceptible to most commercial disinfectants, antiseptics, and detergents. In the environment, it is inactivated at 37ºC for 3 hours or in 5 minutes at 56ºC. At 4ºC, the virus remains infectious for at least 5 months and at 25ºC for about 1 month (4).

Epidemiology

The domestic cat is the main host and reservoir of feline herpesvirus, although it has also been isolated in lions and cheetahs. The virus is spread through oronasal and conjunctival secretions by acutely infected cats and latently infected cats that experience reactivation of the disease, and transmission occurs mainly by direct contact between infected and susceptible cats. Transmission by environmental contamination is not very common, except in catteries (4).

Transplacental transmission has not been demonstrated. However, mothers can infect their offspring because birth and lactation are stressful situations that can lead to reactivation and spread of the virus. The outcome of the infection will depend on the level of maternally derived antibodies that the offspring have. If they have high levels, they will be protected from the disease and develop a subclinical infection that leads to latency. If the level of maternal antibodies is low, they will develop clinical signs (4).

Morbidity can reach 100% in young cats and those found in large populations such as catteries. Mortality can be high in juveniles and debilitated cats, and can reach 50% associated with generalized infection (5).

Pathogenesis

Primary infection is most common in kittens when maternal antibodies decline around 8 weeks of age and juvenile individuals (6-24 months). Feline herpesvirus type 1 has a preference for infecting mucoepithelial cells of the tonsils, conjunctiva, and nasal mucosa, although there is also significant infection of corneal epithelial cells (3).

This results in a lytic infection characterized by rapid replication and acute cell damage leading to cytolysis. Clinical signs develop 2-6 days after infection. The ocular signs associated with this phase (conjunctivitis and epithelial keratitis) are characterized by the formation of persistent punctate epithelial and dendritic ulcers (3).

The virus spreads to sensory nerves, primarily in the trigeminal ganglion, which are the sites where the virus will enter latency (4). The latent virus can reactivate and cause a flare of clinical disease. This situation can occur spontaneously or in association with various stressors, including systemic administration of corticosteroids, co-infection with other pathogens, rehousing, parturition and lactation (3).

Clinical signs

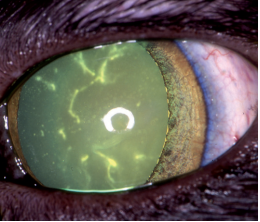

Feline herpesvirus type 1 infection typically causes upper respiratory tract disease and ocular disease, which can be severe in kittens. Erosion and ulceration of mucosal surfaces, rhinitis and conjunctivitis frequently occur. Occasionally, corneal dendritic ulcers characteristic of the disease can be seen (Figure 1) (4).

Figure 1: Ulcerative dendritic keratitis in acute feline herpesvirus infection

Source: Thiry et al., Feline herpesvirus infection. ABCD guidelines on prevention and management (2009).

The usual clinical signs are fever, depression, anorexia, ocular discharge, nasal discharge, serous or serosanguineous nasal or ocular discharge, conjunctival hyperemia, sneezing and, less frequently, salivation and cough. Secondary bacterial infections are common and secretions become purulent (Figure 2) (4).

Figure 2: Ocular lesion with secondary bacterial infection

Source: Thiry et al., Feline herpesvirus infection. ABCD guidelines on prevention and management (2009).

Primary pneumonia and a viraemic state may occur in particularly susceptible kittens, which may produce severe generalized signs leading to death. Less frequently, oral and skin ulcers, dermatitis and neurological signs may be seen (4).

Diagnosis

Clinically, there is similarity between the signs of feline herpesvirus type 1 and feline calicivirus, which is another important respiratory disease in cats. Distinguishing features of FHV-1 are high fever and corneal ulcerations. In contrast, ulcers on the tongue, palate and pharynx are more common in calicivirus infections (2).

The most common diagnostic methods to demonstrate the presence of FHV-1 or its viral components in tissue homogenates or swabs are the direct fluorescent antibody test, virus isolation, and PCR (2).

The direct fluorescent antibody test is performed on conjunctival or corneal tissue, although it is increasingly used less. Viral isolation and PCR using oronasal or conjunctival samples are currently more commonly used. Viral isolation is considered the gold standard (2).

Treatment

In cats with severe clinical signs, fluid, electrolyte, and pH replacement is important, preferably intravenously. Many cats refuse to eat due to oral ulcers (if present, although this is not common) or loss of sense of smell, so highly palatable food should be offered and heated to enhance flavor. Appetite stimulants can be used to help with this task. If the animal continues to refuse to eat for at least 3 days, a feeding tube should be placed (4).

To prevent bacterial infections in acute disease, the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics that can penetrate the respiratory tract is important (4). The use of doxycycline has shown clinical improvement in cats with upper respiratory tract disease due to its action against Mycoplasma felis, Bordetella bronchiseptica and Chlamydia felis (6).

The use of some antivirals is recommended for the treatment of feline herpesvirus type 1, of which trifluridine has shown the greatest efficacy due to its potency and penetration into the cornea. Idoxuridine has shown the second greatest efficacy in addition to being less irritating. These drugs are administered topically for the treatment of FHV-1 with ocular manifestations (2).

A study by Malik et al. suggests that oral administration of famciclovir is safe and effective for the treatment of ocular signs, skin disease, and FHV-1-induced rhinitis (1).

Control and prevention

It is important that all cats be vaccinated against feline herpesvirus because, while these vaccines do not necessarily prevent infection, they do reduce the severity of clinical disease, viral shedding, and the consequences of viral recrudescence (3).

Maternal antibodies provide some degree of humoral protection in kittens up to approximately 8 weeks of age, so primary vaccination should be started at around 9 weeks of age as maternal immunity may interfere with the response. Although some vaccines are licensed for earlier use, they should then receive a second vaccination 2 to 4 weeks later, at around 12 weeks of age. For adult cats whose vaccination status is unknown, two vaccinations should still be given at an interval of 2 to 4 weeks. An annual booster is recommended, especially for cats in high-risk situations or environments (3) (4).

In shelters, FHV-1 is a constant problem, so management measures to limit or contain infection are as important as vaccination. Each new cat entering the shelter must undergo a 2-week quarantine period and be kept individually, unless they come from the same place (4).

Conclusions

The ocular and respiratory disease caused by feline herpesvirus type 1 is of special importance due to the clinical signs it causes in cats, especially in younger ones, where it can even cause death.

This virus remains latent after the initial infection, so it will reactivate when the cat faces stressful conditions. This is why the best way to avoid future health problems is through prevention. Vaccination will reduce the severity of the clinical disease if the animal is exposed to the virus at some point.